Management of Bladder Pain Syndrome

Green-top Guideline No. 70

This is the first edition of this guideline.

Executive summary of recommendations

Initial presentation and assessment

What initial clinical assessment should be performed?

Bladder pain syndrome (BPS) is a chronic pain syndrome and the principles of management of chronic pain should be used for the initial assessment of this condition.

Grade of recommendation: C

A thorough medical history should be taken and physical examination performed.

Grade of recommendation: ✓

What baseline investigations should be performed?

A bladder diary (frequency volume chart) should be completed.

Grade of recommendation: ✓

A food diary may be used to identify if specific foods cause a flare-up of symptoms.

Grade of recommendation: ✓

Urine should be tested to rule out a urinary tract infection as this is a prerequisite for diagnosis of BPS. Investigations for urinary ureaplasma and chlamydia can be considered in symptomatic patients with negative urine cultures and pyuria.

Grade of recommendation: C

In those with a suspicion of urological malignancy, urine cytology should be tested. Cystoscopy and referral to urology should be initiated in accordance with local protocols.

Grade of recommendation: C

Diagnosis of BPS

What are the differential diagnoses?

BPS is a diagnosis of exclusion and other conditions should be excluded.

Grade of recommendation: D

What investigations are used to diagnose BPS?

Bladder biopsies and hydrodistention are not recommended for the diagnosis of BPS. Cystoscopy does not confirm or exclude the diagnosis of BPS, but is required to diagnose/exclude other conditions that mimic BPS.

Grade of recommendation: ✓

Potassium sensitivity test, urodynamic assessment and urinary biomarkers should not be used in the diagnosis of BPS. Urodynamic tests may be considered if there is coexisting BPS and overactive bladder (and/or stress urinary incontinence and/or voiding dysfunction) that are not responsive to treatment.

Grade of recommendation: C

How can we classify the severity of BPS?

Clinicians should use a validated symptom score to assess baseline severity of BPS and assess response to treatment.

Grade of recommendation: B

The use of visual analogue scales for pain should be considered to assess severity of pain in BPS.

Grade of recommendation: D

What is the effect of BPS on quality of life (QoL)?

Patients with BPS can have low self-esteem, sexual dysfunction and reduced QoL.

Grade of recommendation: C

Patients with BPS may have other coexistent conditions impacting on their QoL.

Grade of recommendation: D

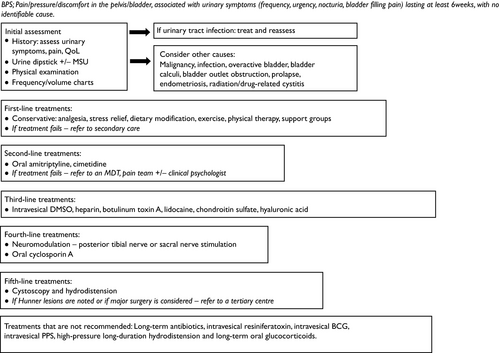

What is the initial management? (see Appendix IV)

Conservative treatments

Dietary modification can be beneficial and avoidance of caffeine, alcohol, and acidic foods and drinks should be considered.

Grade of recommendation: D

Stress management may be recommended and regular exercise can be beneficial.

Grade of recommendation: D

Analgesia is recommended for the symptom of pelvic or bladder pain.

Grade of recommendation: ✓

There are limited data on the benefits of acupuncture.

Grade of recommendation: D

Pharmacological treatments

Oral amitriptyline or cimetidine may be considered when first-line conservative treatments have failed. Cimetidine is not licensed to treat BPS and should only be commenced by a clinician specialised to treat this condition.

Grade of recommendation: B

Intravesical treatments

If conservative and oral treatments have been unsuccessful, other therapies may be added or substituted using an individualised approach. This will depend on the experience and expertise of the clinical team involved, and onward referral to a specialist centre with expertise in chronic pain management and access to professionals from other specialties to provide a multidisciplinary approach to care may be appropriate. Options include:

Intravesical lidocaine.

Grade of recommendation: B

Intravesical hyaluronic acid.

Grade of recommendation: B

Intravesical injection of botulinum toxin A (Botox).

Grade of recommendation: B

Intravesical dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO).

Grade of recommendation: C

Intravesical heparin.

Grade of recommendation: D

Intravesical chondroitin sulfate.

Grade of recommendation: D

Further treatment options

Further options should only be considered after referral to a pain clinic and discussion at a multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting.

Grade of recommendation: ✓

Cystoscopic fulguration and laser treatment, and transurethral resection of lesions can be considered if Hunner lesions are identified at cystoscopy.

Grade of recommendation: ✓

Neuromodulation (nerve stimulation), in the form of posterior tibial or sacral neuromodulation, may be considered after conservative, oral and/or intravesical treatments have failed, in a multidisciplinary setting.

Grade of recommendation: D

Oral cyclosporin A may be considered after conservative, other oral, intravesical and neuromodulation treatments have failed.

Grade of recommendation: D

Cystoscopy with or without hydrodistension may be considered if conservative and oral treatments have failed.

Grade of recommendation: D

Major surgery may be considered as last-line treatment in refractory BPS.

Grade of recommendation: D

Treatments that are not recommended

Oral hydroxyzine does not appear to be an effective treatment for BPS.

Grade of recommendation: B

Oral pentosan polysulfate does not appear to be an effective treatment for BPS.

Grade of recommendation: A

Long-term antibiotics, intravesical resiniferatoxin, intravesical Bacillus Calmette–Guérin, high-pressure long-duration hydrodistension and long-term oral glucocorticoids are therapies that are not recommended for BPS.

Grade of recommendation: ✓

Further management (see Appendix IV)

Who should manage BPS?

History, urinalysis and physical examination should be carried out in primary care.

Grade of recommendation: ✓

Who should be referred to secondary care?

Patients who fail to respond to conservative treatment should be referred to secondary care.

Grade of recommendation: ✓

What is the role of the MDT – physiotherapist, pain team, clinical psychologist?

Referral to a physiotherapist should be considered as BPS symptoms may be improved with physical therapy.

Grade of recommendation: B

Consider referring patients with refractory BPS for psychological support or counselling if it is impacting on their QoL or the patient requests a referral.

Grade of recommendation: ✓

Patients with refractory BPS should be referred to an MDT in order to explore alternative treatment options. Those patients who may benefit from neuromodulation should be referred to an MDT before treatment is commenced.

Grade of recommendation: ✓

What is the role of support groups?

Patients should be given written information about patient organisations that provide evidence-based information.

Grade of recommendation: ✓

Long-term management and prognosis

What should be the duration of follow-up?

Patients should be followed up periodically in secondary care with consideration for shared care between the pain team and urogynaecology until symptoms become controlled and then they can be followed in primary care if required.

Grade of recommendation: ✓

BPS and pregnancy

Woman can be advised that the effect of pregnancy on the severity of BPS symptoms can be variable.

Grade of recommendation: ✓

BPS treatment options considered safe in pregnancy include oral amitriptyline and intravesical heparin.

Grade of recommendation: ✓

Although one course of DMSO may be used prior to pregnancy for symptom remission with good pregnancy outcomes (delivery at term, normal birth weight and postnatal symptom control), DMSO is known to be teratogenic in animal studies.

Grade of recommendation: D

1 Purpose and scope

This guideline aims to provide evidence-based information for primary and secondary care clinicians on the symptoms and treatment options for bladder pain syndrome (BPS) in women, together with an appreciation of the current uncertainties surrounding this condition.

2 Definition and epidemiology

The widespread definition for BPS is that proposed by the European Society for the Study of BPS (ESSIC) in 20081 as ‘pelvic pain, pressure or discomfort perceived to be related to the bladder, lasting at least 6 months, and accompanied by at least one other urinary symptom, for example persistent urge to void or frequency, in the absence of other identifiable causes’. More recently, the American Urological Association2 has described BPS as ‘an unpleasant sensation (pain, pressure, discomfort) perceived to be related to the urinary bladder, associated with lower urinary tract symptoms of more than 6 weeks duration, in the absence of infection or other identifiable causes’; this definition is preferable as it allows treatments to be initiated soon after symptom presentation. BPS may be associated with negative cognitive, behavioural, sexual or emotional consequences, as well as symptoms suggestive of sexual dysfunction according to the European Association of Urology.

The term BPS has been recommended rather than the previous names of interstitial cystitis (IC) and painful bladder syndrome. IC was first described in 1887 by Skene and in 1914 Hunner described the nontrigonal ulcers and bladder epithelial damage, known as ‘Hunner's ulcers’.3 More recently, these are referred to as Hunner lesions. In 1987, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases,4 one of the US National Institutes of Health, developed diagnostic criteria for the condition with the following inclusions: pain associated with bladder or urinary frequency, and glomerulations (pinpoint petechial haemorrhages) on cystoscopy or classic Hunner lesions seen after hydrodistension under anaesthesia to 80–100 cm water pressure for 1–2 minutes, where the glomerulations must be diffuse and present in at least three quadrants of the bladder at a rate of at least 10 per quadrant and not along the path of the cystoscope as this may be an artefact. Hunner lesions may be seen as inflamed friable areas or nonblanching areas in the chronic state. These strict criteria meant many patients were underdiagnosed so a new term, painful bladder syndrome, was proposed in 2002 by the International Continence Society as ‘suprapubic pain related to bladder filling, accompanied by other symptoms, such as increased daytime and night-time frequency, in the absence of any identifiable pathology or infection’. The International Continence Society reserved the diagnosis of IC to patients ‘with typical cystoscopic and histological features’.5

BPS is a chronic condition with unknown aetiology. Cystoscopic findings have been omitted from the 2008 definition, as positive findings, such as glomerulations, have been found in asymptomatic patients and inclusion of cystoscopic findings into the disease criteria runs the risk of excluding symptomatic patients. As the definition of BPS has evolved, it is seen now as a diagnosis of exclusion with no definitive diagnostic test; hence, it is difficult to estimate prevalence, which can be dependent on whether symptoms are clinician assigned or patient reported. A large American study6 found prevalence rates of 2.3–6.5%. BPS is between two and five times more common in women than men.7-9 A systematic review found the most commonly reported symptoms of BPS to be bladder/pelvic pain, urgency, frequency and nocturia.10 A number of expert panels, including the ESSIC,1 American Urological Association,2 European Association of Urology11 and International Consultation on Incontinence,12 have published symptom-based diagnostic criteria for BPS. All include the symptoms of pain related to the bladder, at least one other urinary symptom, absence of identifiable causes and minimum duration of symptoms of 6 weeks2 to 6 months. Although there are very limited data on BPS in the UK, a survey of urogynaecologists13 has shown variable practice regarding its diagnosis and management.

3 Identification and assessment of evidence

This guideline was developed in accordance with standard methodology for producing Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) Green-top Guidelines. MEDLINE, EMBASE and the Cochrane Library were searched. The search was restricted to articles published between 2006 and October 2015 and limited to humans and the English language. The databases were searched using the relevant Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms, including all subheadings, and this was combined with a keyword search. Search terms included ‘bladder pain syndrome’, ‘interstitial cystitis’, ‘painful bladder syndrome’, ‘pelvic pain’ and ‘urogynaecology’. The National Guideline Clearinghouse, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Evidence Search, Trip and Guidelines International Network were also searched for relevant guidelines.

Where possible, recommendations are based on available evidence. Areas lacking evidence are highlighted and annotated as ‘Good Practice Points’. Further information about the assessment of evidence and the grading of recommendations may be found in Appendix I.

4 Initial presentation and assessment

4.1 What initial clinical assessment should be performed?

BPS is a chronic pain syndrome and the principles of management of chronic pain should be used for the initial assessment of this condition.

Grade of recommendation: C

A thorough medical history should be taken and physical examination performed.

Grade of recommendation: ✓

The initial consultation is aimed at generating trust between the patient and the caregiver. In chronic pain syndromes, it is well recognised that a favourable patient rating of the initial consultation is associated with greater likelihood of complete recovery at follow-up.14 Patients should be encouraged to talk about their symptoms and any theories that they have about the origins of the pain. This allows engagement in further investigations and management of their condition.15, 16 It is important to explain that BPS is a chronic condition with periods of fluctuating symptom severity, where symptoms may be life-long. Symptom assessment forms the basis of the initial evaluation. This is discussed in section 5.3. The location of the pain has been described in several studies and the most commonly reported sites are the bladder, urethra and vagina. The description of the pain ranges from pressure and aching to a burning sensation. A study of 565 patients with the condition was used to identify factors that can aggravate and alleviate the condition. Voiding was found to relieve the pain in 57–73% of patients. Pain was aggravated by stress (61%), sexual intercourse (50%), constrictive clothing (49%), acidic beverages (54%), coffee (51%) and spicy foods (46%). The Events Preceding IC study of 158 women with BPS17-19 found that pain worsened with certain food or drink, and/or worsened with bladder filling, and/or improved with urination in 97% of patients. As the diagnosis of BPS is one of exclusion, it is important to rule out other possible causes of bladder pain. The history taken should include details of previous pelvic surgery, urinary tract infections (UTIs), sexually transmitted infections, bladder disease and autoimmune disease. Other conditions commonly associated with BPS, such as irritable bowel syndrome, vulvodynia, endometriosis, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome and autoimmune diseases like systemic lupus erythematosus and Sjögren's syndrome, should be enquired about while taking a clinical history. The location of the pain, and relationship to bladder filling and emptying should be established. The characteristics of the pain, including trigger factors and onset, correlation with other events and description of the pain, should be recorded. It should be explored whether the woman has any history of physical or sexual abuse as this can be associated with pelvic pain.20 This can be achieved using preformed questionnaires as this can be a sensitive topic. Information should be sought about prior or current use of oral contraception, which a systematic review21 has shown may be associated with BPS symptoms. |

Evidence level 3 |

| Physical examination should be aimed at ruling out bladder distension due to urinary retention, hernias and painful trigger points on abdominal palpation. A genital examination should be performed to rule out atrophic changes, prolapse, vaginitis and trigger point tenderness over the urethra, vestibular glands, vulvar skin or bladder. Features of dermatosis, including vulvar or vestibular disease, should be looked for. An evaluation of the introitus and tenderness during insertion or opening of the speculum should be made. Superficial/deep vaginal tenderness and tenderness of the pelvic floor muscles should be assessed during the course of the examination. Cervical pathology should be excluded. A bimanual pelvic examination is helpful to rule out abdominal, cervical or adnexal pathology. | Evidence level 4 |

4.2 What baseline investigations should be performed?

A bladder diary (frequency volume chart) should be completed.

Grade of recommendation: ✓

A food diary may be used to identify if specific foods cause a flare-up of symptoms.

Grade of recommendation: ✓

Urine should be tested to rule out a UTI as this is a prerequisite for diagnosis of BPS. Investigations for urinary ureaplasma and chlamydia can be considered in symptomatic patients with negative urine cultures and pyuria.

Grade of recommendation: C

In those with a suspicion of urological malignancy, urine cytology should be tested. Cystoscopy and referral to urology should be initiated in accordance with local protocols.

Grade of recommendation: C

A 3-day fluid diary with input and output is useful for initial assessment (for an example diary see Appendix II). Patients with BPS classically void small volumes, so this is useful to identify the severity of the storage symptoms. The first morning void is a useful guide to the functional capacity of the bladder. The bladder diary can also be used to reinforce behavioural strategies and, where necessary, pharmacological treatment. Estimation of residual urine volumes after an episode of micturition should be assessed using bladder scans as part of initial investigations if there are concerns about incomplete bladder emptying.

Maintaining a diary to record food intake and its association with pain can be useful to identify if certain types of food cause symptoms to flare up.

A dipstick should be performed and where there is a suggestion of a UTI, a culture and sensitivity test should be obtained with consideration given to testing for acid-fast bacilli where there is sterile pyuria. Other more common causes of sterile pyuria that should be considered are urinary tract stones, partially treated UTIs and carcinoma in situ of the bladder. Ureaplasma is not isolated in routine culture tests, so would need to be specifically looked for.

A study of 92 patients diagnosed with BPS22 demonstrated that the condition itself was not associated with persistence of bacterial or viral DNA on bladder biopsy which were negative for adenovirus, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus types I and II, human papillomavirus (all subtypes) and Chlamydia trachomatis. These findings exclude a chronic infective aetiology for the condition. A separate study,23 looking at the clinical characteristics of 87 women with the condition, found that 12% had a past history of chlamydia and therefore, it is important to rule this out with appropriate investigations. In the presence of persistent microscopic haematuria, urine cytology is usually indicated and cystoscopy considered. Persistent microscopic haematuria should be managed in accordance with local protocols for investigating haematuria. In a study of 148 patients with BPS,24 at least one episode of haematuria was reported in 41% of cases over the preceding 18 months. In this group, of those who agreed to a full evaluation, no cases of malignancy were identified. No statistically significant differences were found in age, bladder capacity, presence of Hunner lesions or glomerulations between patients with haematuria and those without. |

Evidence level 2– |

5 Diagnosis of BPS

5.1 What are the differential diagnoses?

BPS is a diagnosis of exclusion and other conditions should be excluded.

Grade of recommendation: D

ESSIC has published a list of differential diagnoses, by expert consensus.1 These include:

Ketamine is used as a recreational drug due to its hallucinogenic effects. Unfortunately, its abuse has led to ketamine cystitis, where the bladder becomes ulcerated and fibrosed with urinary tract symptoms, such as frequency, urgency and haematuria, along with renal impairment. |

Evidence level 4 |

5.2 What investigations are used to diagnose BPS?

Bladder biopsies and hydrodistention are not recommended for the diagnosis of BPS. Cystoscopy does not confirm or exclude the diagnosis of BPS, but is required to diagnose/exclude other conditions that mimic BPS.

Grade of recommendation: ✓

Potassium sensitivity test, urodynamic assessment and urinary biomarkers should not be used in the diagnosis of BPS. Urodynamic tests may be considered if there is coexisting BPS and overactive bladder (and/or stress urinary incontinence and/or voiding dysfunction) that are not responsive to treatment.

Grade of recommendation: C

Cystoscopy without hydrodistension is expected to be normal (except for discomfort and reduced bladder capacity) in the majority of patients with BPS.

Characteristic cystoscopic findings that have been ascribed to BPS include post distension glomerulations, reduced bladder capacity and bleeding. Cystoscopy may be used to aid in classifying BPS (Appendix III). However, cystoscopy findings correlate poorly with symptoms. In the IC Database Study,25 150 women underwent cystoscopy and hydrodistension, and there was no correlation observed between severity of symptoms and the finding of glomerulations or bleeding following hydrodistension. Pain, urgency and reduced bladder capacity were associated with the presence of Hunner lesions in 11.7% of the women. Similar findings have been reported in other studies26, 27 along with glomerulations in asymptomatic women. Pathological features have been described in patients with BPS, including inflammatory infiltrates, detrusor mastocytosis, granulation tissue and fibrosis, but these are nonspecific. The diagnosis of BPS cannot be made or excluded on the basis of any specific finding on bladder biopsy, and these features are not required for the diagnosis. In a study of 108 people with BPS,28 no correlation was found between histological and cystoscopic findings. In an earlier study of 50 patients,29 there was a correlation with reduced bladder capacity, inflammation and mast cell count; however, cystoscopic and histological findings showed large variation. Bladder biopsy may be used to classify BPS (Appendix III) or may be indicated to exclude other pathologies, such as carcinoma in situ, if suspected by a focal lesion or abnormal cytology. Hunner lesions are present in type 3 BPS and can be associated with reduced bladder capacity. |

Evidence level 2– |

| Caution should be exercised as there is the recognised risk of bladder perforation and rupture associated with cystoscopy and hydrodistension.30 | Evidence level 3 |

| During urodynamic studies, pain on bladder filling, a reduced first sensation to void and reduced bladder capacity are consistent with BPS; however, there are no urodynamic criteria that are diagnostic for BPS. The presence of detrusor overactivity, which is seen in approximately 14% of patients with BPS, should not preclude a diagnosis of BPS.31 Pressure flow studies may be considered in patients where there are coexisting voiding symptoms, but are not recommended for the diagnosis of BPS.32 | Evidence level 2– |

Any suspected additional pelvic or abdominal pathology should be appropriately investigated.

5.3 How can we classify the severity of BPS?

Clinicians should use a validated symptom score to assess baseline severity of BPS and assess response to treatment.

Grade of recommendation: B

The use of visual analogue scales for pain should be considered to assess severity of pain in BPS.

Grade of recommendation: D

| Symptom scores can be used to grade the severity of BPS and assess response to treatment. There are three published BPS symptom questionnaires: the University of Wisconsin IC Scale,33 the O'Leary-Sant IC Symptom Index and IC Problem Index,34 and the Pelvic Pain and Urgency/Frequency Scale.17 All have been validated in patients with BPS, and the University of Wisconsin IC Scale, and the O'Leary-Sant IC Symptom Index and IC Problem Index have shown responsiveness to change over time.32 In a comparison of questionnaires used for the evaluation of chronic pelvic pain, there was a good correlation between the IC Symptom Index, and the Pelvic Pain and Urgency/Frequency symptom scores for bladder complaints, but poor correlation for quality of life (QoL).35 | Evidence level 2++ |

| A number of different rating scales have been devised to measure pain, such as numerical rating scores or the McGill pain questionnaire.36 The rating scales rely on a subjective assessment of the pain. Although a visual analogue scale is an easily administered instrument to capture pain intensity, a pain-related QoL measure, such as the brief pain inventory, gives a far better assessment of baseline pain and response to treatment.37 | Evidence level 3 |

6 What is the effect of BPS on QoL?

Patients with BPS can have low self-esteem, sexual dysfunction and reduced QoL.

Grade of recommendation: C

Patients with BPS may have other coexistent conditions impacting on their QoL.

Grade of recommendation: D

| Patients will often be highly anxious about their symptoms and may present with low self-esteem and poor QoL.38 Women with BPS can present with sexual dysfunction.39 Partner and family support are important and early referral to a clinical psychologist, patient support groups and cognitive behavioural therapy should be considered for persistent BPS. QoL can be assessed formally using questionnaires, such as the King's Health Questionnaire, EuroQoL or Short Form-36 Health Survey. | Evidence level 2– |

7 What is the initial management? (see Appendix IV)

7.1 Conservative treatments

Dietary modification can be beneficial and avoidance of caffeine, alcohol, and acidic foods and drinks should be considered.

Grade of recommendation: D

Stress management may be recommended and regular exercise can be beneficial.

Grade of recommendation: D

Analgesia is recommended for the symptom of pelvic or bladder pain.

Grade of recommendation: ✓

There are limited data on the benefits of acupuncture.

Grade of recommendation: D

A survey of 1982 participants with IC42 revealed that 87.6% of patients reported symptomatic improvement with an elimination diet and 86.1% by complete avoidance of comestibles outlined in a paper by Shorter et al.,43 although treatment duration was not specified. Certain foods that worsen pain are alcohol, citrus fruits, coffee, carbonated drinks, tea, chocolate and tomatoes.18 If dietary modifications do not help symptoms, these foods can be reintroduced. In the same survey,42 76.4% of patients reported symptomatic improvement using relaxation techniques, 66.8% using meditation, 64.5% listening to music and 80.5% with stress reduction. In addition, 65.2% of patients reported symptomatic improvement with regular exercise. |

Evidence level 3 |

| Between 30% and 61% of patients presenting with chronic pelvic pain have BPS, so although there are no data available about the efficiency of different forms of analgesia in the treatment of BPS, simple analgesia, such as paracetamol and ibuprofen, may be useful at treating the key symptom of pain in this condition.40, 44 However, opioids should be used with caution as there is little evidence they are useful for long-term chronic pain. Early referral to a pain clinic should be considered for patients with refractory symptoms.45 | Evidence level 4 |

| A systematic review of three observational studies with a total of 22 patients46 suggested that acupuncture provided moderate symptomatic improvement; however, these are very small numbers and a large randomised trial is needed to properly evaluate treatment effectiveness. | Evidence level 3 |

7.2 Pharmacological treatments

Oral amitriptyline or cimetidine may be considered when first-line conservative treatments have failed. Cimetidine is not licensed to treat BPS and should only be commenced by a clinician specialised to treat this condition.

Grade of recommendation: B

A systematic review47 of two randomised controlled trials (RCTs)48, 49 that included a total of 281 patients who were treated with increasing titrated doses of amitriptyline between 10 mg and 100 mg over a 4-month period showed trends in improvement in urinary urgency, frequency and pain scores in both trials compared with nontreated patients. However, these were only statistically significant in the smaller study of 48 patients.49 Compliance is often affected by the adverse effects, which include dry mouth, constipation, sedation, weight gain and blurred vision. One RCT50 compared 36 patients treated with a 3-month course of 400 mg cimetidine orally versus placebo twice daily. All patients had symptomatic improvements, but these were more pronounced in the treatment group, especially for pain and nocturia. The small sample size and short duration of follow-up are limiting factors in this study. Cimetidine is currently not licensed for the treatment of BPS. |

Evidence level 1– |

Multimodal therapy may be considered if single drugs are unsuccessful, but should be commenced by consultants with special expertise and consideration of multidisciplinary input.

7.3 Intravesical treatments

If conservative and oral treatments have been unsuccessful, other therapies may be added or substituted using an individualised approach. This will depend on the experience and expertise of the clinical team involved, and onward referral to a specialist centre with expertise in chronic pain management and access to professionals from other specialties to provide a multidisciplinary approach to care may be appropriate. Options include:

Intravesical lidocaine.

Grade of recommendation: B

Intravesical hyaluronic acid.

Grade of recommendation: B

Intravesical injection of botulinum toxin A (Botox).

Grade of recommendation: B

Intravesical dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO).

Grade of recommendation: C

Intravesical heparin.

Grade of recommendation: D

Intravesical chondroitin sulfate.

Grade of recommendation: D

Lidocaine is a local anaesthetic that acts by blocking sensory nerve fibres in the bladder. One RCT51 reported on 102 patients treated with a 5-day course of 200 mg intravesically administered lidocaine with alkalinised instillation of 8.4% sodium bicarbonate to a final volume of 10 ml versus placebo. Over a 29-day follow-up period, 30% of treated patients compared with 9.6% of the control group reported symptomatic improvement.52 A systematic review of controlled and observational studies evaluated hyaluronic acid, for example, Cystistat® (Teva UK Limited, Castleford, Yorkshire) given in a weekly regimen for up to 4–10 weeks, with varying follow-up times. It appears to be an effective intravesical treatment with a number needed to treat of 1.31.53 |

Evidence level 1– |

| A systematic review54 evaluating intravesical injection of Botox in BPS patients found three RCTs55-57 and seven prospective cohort studies58-64 with a total of 260 patients. Eight of these studies reported symptomatic improvement,55, 56, 58-61, 63, 64 although, 7% of patients needed post-treatment self-catheterisation. Clinicians and patients might consider trying bladder instillations before resorting to invasive treatments like Botox injections into the bladder, including the trigone. For this reason, it should be performed by a consultant with a special interest in this clinical field. | Evidence level 2++ |

| A systematic review65 of pharmacological managements of BPS identified one randomised crossover study66 that evaluated 33 patients given placebo (saline) or 50% DMSO for two sessions each week for 2 weeks. Of the treatment group, 53% had marked symptomatic improvement compared with 18% of the placebo group. Adverse effects include a garlic-like taste and odour on the breath and skin, and bladder spasm. Full eye examination is needed prior to starting treatment and 6-monthly blood tests for renal, liver and full blood counts are advised. This treatment may not be offered in all hospitals in the UK as it is an unlicensed treatment that needs to be prescribed by a consultant with special expertise in this clinical field. For this reason, referral to a specialised centre would be recommended. | Evidence level 2+ |

One observational study67 evaluated 48 patients treated with 10 000 units of heparin in 10 ml sterile water instilled three times a week for 3 months. The study reported that 56% of patients achieved clinical remission over 3 months and 50% of patients had symptomatic control after 1 year. An individual participant meta-analysis of 213 patients68 showed some benefit in the global response assessment using 2% intravesical chondroitin sulfate. Small observational studies of 43 patients69-71 have shown symptomatic improvement using a combination of intravesical hyaluronic acid and chondroitin sulfate, with data suggesting a sustained effect for up to 3 years. Use of multimodal therapies needs to be initiated with specialist clinicians after multidisciplinary input. |

Evidence level 3 |

7.4 Further treatment options

Further options should only be considered after referral to a pain clinic and discussion at a multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting.

Grade of recommendation: ✓

Cystoscopic fulguration and laser treatment, and transurethral resection of lesions can be considered if Hunner lesions are identified at cystoscopy.

Grade of recommendation: ✓

Neuromodulation (nerve stimulation), in the form of posterior tibial or sacral neuromodulation, may be considered after conservative, oral and/or intravesical treatments have failed, in a multidisciplinary setting.

Grade of recommendation: D

Oral cyclosporin A may be considered after conservative, other oral, intravesical and neuromodulation treatments have failed.

Grade of recommendation: D

Cystoscopy with or without hydrodistension may be considered if conservative and oral treatments have failed.

Grade of recommendation: D

Major surgery may be considered as last-line treatment in refractory BPS.

Grade of recommendation: D

Hunner lesions do not respond to oral treatments and need surgical management. They are usually diagnosed by cystoscopy with the appearance of a well-demarcated, reddish, mucosal lesion lacking in the normal capillary structure, which usually bleeds.72 Two observational studies73, 74 reported success when using Nd:YAG (neodymium:yttrium-aluminium-garnet) laser under cystoscopic control in patients with BPS with Hunner lesions. Fifty-one patients were treated, resulting in 88% symptomatic relief within 2–3 days of treatment; however, 45% needed additional treatment within 23 months. Since these lesions do not usually respond to oral treatments, fulguration and resection should be considered at an early stage. Posterior tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS) is likely to require a fine needle being inserted 5 cm cephalad from the medial malleolus and posterior to the margin of the tibia at the site of the posterior tibial nerve. The treatment regimen is usually weekly for 10–12 weeks.75 Sacral nerve modulation involves an initial test phase with insertion of a test lead tunnelled under the skin, transmitted onto the nerve roots exiting the S3 foramen, causing stimulation of the pelvic and pudendal nerves. The lead is connected to a stimulator which is exchanged for a permanent implant if successful.76 There are no RCTs evaluating either form of neuromodulation. Effectiveness data come from observational studies. One study reported efficacy of PTNS in 18 patients77 and five studies78-82 reported on sacral nerve stimulation in 150 patients. All studies showed improvements in symptoms and QoL. Both forms of neuromodulation are invasive procedures and are associated with potential risks, although, PTNS is an office-based (outpatient) procedure with no incisions. This treatment should be carried out in centres with expertise at managing chronic pain in a multidisciplinary care setting. One observational study83 of 23 patients treated with low-dose oral cyclosporin showed improvements in bladder capacity, voiding volumes, pain and decreased urinary frequency; however, symptoms recurred with treatment cessation. Adverse effects include hypertension, gingival hyperplasia and facial hair growth. Cystoscopy is recommended as a treatment rather than solely as a diagnostic tool. Three observational studies84-86 have described variable symptomatic improvement. However, within 6 months, symptoms had recurred in the majority of patients.84-86 Bladder rupture is a possible complication of prolonged distension of a diseased bladder; hence, low-pressure distension is advised.30 Total cystectomy and urinary diversion in the form of supratrigonal cystectomy with bladder augmentation, bowel or supratrigonal cystectomy, and orthotopic neobladder formation will likely need intermittent self-catheterisation, and patients must be aware of the likelihood of persistent pelvic and pouch pain post surgery.72 Urinary diversion in the form of an ileal conduit (with or without simple cystectomy) will not require intermittent self-catheterisation.87 This surgery is usually performed in specialist centres by a urologist. A retrospective observational study88 of 47 patients who had reconstructive surgery, including cystectomy, ileocystoplasty and urinary diversion, for BPS found that 82% of patients with Hunner lesions had symptomatic relief after surgery compared with 23% with non-ulcer disease after an average 89-month follow-up period. |

Evidence level 3 |

7.5 Treatments that are not recommended

Oral hydroxyzine does not appear to be an effective treatment for BPS.

Grade of recommendation: B

Oral pentosan polysulfate (PPS) does not appear to be an effective treatment for BPS.

Grade of recommendation: A

Long-term antibiotics, intravesical resiniferatoxin, intravesical Bacillus Calmette–Guérin, high-pressure long-duration hydrodistension and long-term oral glucocorticoids are therapies that are not recommended for BPS.

Grade of recommendation: ✓

One RCT89 of 31 patients treated with oral hydroxyzine 10–50 mg daily in titrated doses for 3 weeks, then treated on the highest effective dose for 21 weeks was compared with a placebo group. There was no significant response rate in the treatment group (31%) versus the control group (20%). PPS is thought to repair the damaged glycosaminoglycan layer, which acts as a protective mechanism for the bladder mucosa.72 An RCT of 368 patients has shown no statistical significance between oral PPS and a placebo.90 PPS has the adverse effects of diarrhoea, vomiting, rectal bleeding and alopecia. In view of this evidence and the adverse effect profile, PPS is no longer recommended as a treatment of BPS. |

Evidence level 1+ |

Long-term antibiotics should not be used as a treatment option. One RCT91 reported on 50 patients randomised to receive an 18-week course of antibiotics (rifampicin plus a sequence of doxycycline, erythromycin, metronidazole, clindamycin, amoxicillin and ciprofloxacin for 3 weeks each) or placebo. There was 48% symptomatic improvement in the treatment group and 24% in the placebo group, but this was not significant. Due to the high rate of adverse effects in the treatment group (80%), these are not recommended. Intravesical resiniferatoxin was evaluated in a systematic review92 of eight RCTs, but failed to show symptomatic improvement and caused pain, which reduced treatment compliance. Intravesical Bacillus Calmette–Guérin has been studied in two RCTs93, 94 on 282 patients compared with a placebo. While it may be effective, there are a large number of adverse effects, including arthralgia, headaches and infection. |

Evidence level 1– |

| High-pressure, long-duration hydrodistension with pressures greater than 80–100 cm of water over more than 10 minutes may cause sepsis or bladder rupture. Two observational studies95, 96 showed a wide range of efficacy rates between 22% and 67%, with at least one case of bladder rupture in each study. The risks of this treatment far outweigh the benefits. | Evidence level 3 |

8 Further management (see Appendix IV)

8.1 Who should manage BPS?

History, urinalysis and physical examination should be carried out in primary care.

Grade of recommendation: ✓

| In primary care, a careful history should be taken enquiring about type, duration and location of pain, urinary symptoms and QoL. Primary care should also check that all conservative measures have been taken. A urine dipstick or midstream specimen of urine is recommended to rule out a UTI. An abdominal and vaginal examination may be performed to assess for tenderness, abdominal masses and urinary retention. Patients should be commenced on first-line conservative treatments, such as analgesia, stress relief, dietary modification, exercise and physical therapy, and if these fail to resolve or improve symptoms, a referral to secondary care should be considered. It is expected that these conservative measures may take between 3 and 6 months to improve symptoms. Referral to a urogynaecologist or urologist with a special interest in BPS would be preferable rather than a general gynaecologist when the main symptoms are pelvic pain and urinary in character. | Evidence level 4 |

8.2 Who should be referred to secondary care?

Patients who fail to respond to conservative treatment should be referred to secondary care.

Grade of recommendation: ✓

Patients should be referred to secondary care after 3–6 months of conservative management if symptoms persist.

8.3 What is the role of the MDT – physiotherapist, pain team, clinical psychologist?

Referral to a physiotherapist should be considered as BPS symptoms may be improved with physical therapy.

Grade of recommendation: B

Consider referring patients with refractory BPS for psychological support or counselling if it is impacting on their QoL or the patient requests a referral.

Grade of recommendation: ✓

Patients with refractory BPS should be referred to an MDT in order to explore alternative treatment options. Those patients who may benefit from neuromodulation should be referred to an MDT before treatment is commenced.

Grade of recommendation: ✓

| An electronic questionnaire42 revealed that 74.2% of patients experienced symptomatic improvement with massage therapy, 61.5% with physical therapy and 66.1% through physical therapy with internal treatment. Internal massage releases the pelvic floor from painful trigger points and areas of myofascial tenderness or restriction. A randomised study99 of 10 scheduled treatments of myofascial physical therapy versus global therapeutic massage on 81 women showed a reduction in pain, frequency and urgency in both groups with no significant difference in therapies. | Evidence level 1– |

Some patients benefit from speaking to a counsellor or clinical psychologist and engaging in behavioural therapy to modify their lifestyles and improve their QoL.

Referral to a pain clinic or clinical psychologist may need to be considered if conservative and oral treatments have failed. This should be considered before commencing intravesical treatments.

8.4 What is the role of support groups?

Patients should be given written information about patient organisations that provide evidence-based information.

Grade of recommendation: ✓

Support groups provide a platform to share experiences, exchange information, raise awareness and promote patient self-help management.

There are many patient organisations that may help patients to find relevant information (see section 12).

9 Long-term management and prognosis

9.1 What should be the duration of follow-up?

Patients should be followed up periodically in secondary care with consideration for shared care between the pain team and urogynaecology until symptoms become controlled and then they can be followed in primary care if required.

Grade of recommendation: ✓

It is difficult to estimate a finite time for follow-up as it is often difficult to achieve symptomatic control to an extent where the patient may be happy, so individualised management plans need to take into consideration response to treatment, effects on QoL and other existing comorbidities.

9.2 BPS and pregnancy

Woman can be advised that the effect of pregnancy on the severity of BPS symptoms can be variable.

Grade of recommendation: ✓

BPS treatment options considered safe in pregnancy include oral amitriptyline and intravesical heparin.

Grade of recommendation: ✓

Although one course of DMSO may be used prior to pregnancy for symptom remission with good pregnancy outcomes (delivery at term, normal birth weight and postnatal symptom control), DMSO is known to be teratogenic in animal studies.

Grade of recommendation: D

| There is little published information about the changes in symptoms that may occur during pregnancy.100 The IC Association conducted a patient survey about symptoms and pregnancy in 1989, where patients who described their symptoms as ‘mild’ experienced worsening symptoms during pregnancy, which persisted up to 6 months after delivery. In contrast, patients who described their symptoms as ‘severe’ had a significant improvement in symptoms during the second trimester, which lasted up to 6 months after delivery or for the duration of breastfeeding. BPS was not affected by the mode of delivery. Another study101 found that only 7% of patients stated that their BPS symptoms had improved during pregnancy. | Evidence level 3 |

Of the commonly used oral treatments, amitriptyline has the lowest risks in pregnancy.100 Heparin is the safest intravesical treatment because it is unlikely to be absorbed from the bladder or to cross the placenta and is not excreted in breast milk. Lidocaine does cross the placenta and there is no information about the safety of chronic exposure to the fetus. Systemic corticosteroids are not known to have teratogenic effects,102, 103 but the possibility of long-term effects on the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis cannot be excluded. The absorption of intravesical corticosteroids is unknown. Sacral nerve stimulators should not be placed during pregnancy and, if already present, should be turned off for the duration of pregnancy as the effect on the fetus is unknown.104 In a few cases, multiple members of the same family have BPS. This suggests that some patients may have a genetic predisposition, however, there is no documented evidence for this. Unless the pregnant patient belongs to a family that has multiple members with the condition, she can be reassured that the risk for passing it on to her child is low.100 |

Evidence level 4 |

| A prospective study105 included 12 patients who had a course of DMSO (every 2 weeks for 12 weeks) and all had symptom remission. Pregnancy occurred 6 months to 5 years after the DMSO treatment. Nine patients continued to have good symptom remission throughout pregnancy. The other three had worsening symptoms and two patients terminated the pregnancy because of severe symptoms. Because this small group of patients was more homogeneous than the general BPS population, with all patients having chronic inflammation on bladder biopsy and good remission after DMSO, it is unclear how the results of this study apply to the general BPS population. DMSO is known to be teratogenic in animal studies and has a US Food and Drug Administration rating of grade C, which states there are no adequate human studies, but animal studies show an increased risk or have not been done.100 In view of this, DMSO should be avoided in pregnancy. | Evidence level 3 |

10 Recommendations for future research

- Create a single, standardised, validated assessment questionnaire.

- Decide on patient-related outcome measures for BPS.

- Assess the role of conservative treatment, e.g. analgesia, dietary modification and stress management (section 7.1), versus placebo for BPS.

- Assess the role of the clinical psychologist.

- Assess the number of patients with coexisting conditions.

- Assess the therapeutic and cost effectiveness of complementary therapies, such as acupuncture, with robustly conducted randomised clinical trials.

11 Auditable topics

- Proportion of patients with BPS symptoms who receive initial conservative treatments in primary care (100%).

- Proportion of patients with BPS who complete a bladder diary for diagnosis (100%).

12 Useful links and support groups

The following organisations provide support for BPS:

- Cystitis and Overactive Bladder Foundation [http://www.cobfoundation.org].

- Pelvic Pain Support Network [http://www.pelvicpain.org.uk].

- International Painful Bladder Foundation [http://www.painful-bladder.org].

- Urostomy Association [http://www.urostomyassociation.org.uk].

Appendix I: Explanation of guidelines and evidence levels

Clinical guidelines are: ‘systematically developed statements which assist clinicians and patients in making decisions about appropriate treatment for specific conditions’. Each guideline is systematically developed using a standardised methodology. Exact details of this process can be found in Clinical Governance Advice No.1 Development of RCOG Green-top Guidelines (available on the RCOG website at http://www.rcog.org.uk/green-top-development). These recommendations are not intended to dictate an exclusive course of management or treatment. They must be evaluated with reference to individual patient needs, resources and limitations unique to the institution and variations in local populations. It is hoped that this process of local ownership will help to incorporate these guidelines into routine practice. Attention is drawn to areas of clinical uncertainty where further research may be indicated.

The evidence used in this guideline was graded using the scheme below and the recommendations formulated in a similar fashion with a standardised grading scheme.

| Classification of evidence levels | Grades of recommendations | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1++ | High-quality meta-analyses, systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials or randomised controlled trials with a very low risk of bias |

|

At least one meta-analysis, systematic reviews or RCT rated as 1++, and directly applicable to the target population; or A systematic review of RCTs or a body of evidence consisting principally of studies rated as 1+, directly applicable to the target population and demonstrating overall consistency of results |

| 1+ | Well-conducted meta-analyses, systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials or randomised controlled trials with a low risk of bias | ||

| 1 – | Meta-analyses, systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials or randomised controlled trials with a high risk of bias |

|

A body of evidence including studies rated as 2++ directly applicable to the target population, and demonstrating overall consistency of results; or Extrapolated evidence from studies rated as 1++ or 1+ |

| 2++ | High-quality systematic reviews of case–control or cohort studies or high-quality case–control or cohort studies with a very low risk of confounding, bias or chance and a high probability that the relationship is causal | ||

| 2+ | Well-conducted case–control or cohort studies with a low risk of confounding, bias or chance and a moderate probability that the relationship is causal |

|

A body of evidence including studies rated as 2+ directly applicable to the target population, and demonstrating overall consistency of results; or Extrapolated evidence from studies rated as 2++ |

| 2– | Case–control or cohort studies with a high risk of confounding, bias or chance and a significant risk that the relationship is not causal |

|

Evidence level 3 or 4; or Extrapolated evidence from studies rated as 2+ |

| 3 | Non-analytical studies, e.g. case reports, case series | Good practice point | |

| 4 | Expert opinion |

|

Recommended best practice based on the clinical experience of the guideline development group |

Appendix II: Example of a bladder diary (adapted from The British Association of Urological Surgeons)

| Time | Liquid intake (ml) | Volume of urine passed (ml) | Urine leaks (small, moderate, large amount) | Urgency (strong, moderate, mild desire) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 00.00 | ||||

| 01.00 | ||||

| 02.00 | ||||

| 03.00 | ||||

| 04.00 | ||||

| 05.00 | ||||

| 06.00 | ||||

| 07.00 | ||||

| 08.00 | ||||

| 09.00 | ||||

| 10.00 | ||||

| 11.00 | ||||

| 12.00 | ||||

| 13.00 | ||||

| 14.00 | ||||

| 15.00 | ||||

| 16.00 | ||||

| 17.00 | ||||

| 18.00 | ||||

| 19.00 | ||||

| 20.00 | ||||

| 21.00 | ||||

| 22.00 | ||||

| 23.00 |

Appendix III: Classification of bladder pain syndrome1 according to cystoscopy and biopsy findings

| Cystoscopy with hydrodistension | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not done | Normal | Glomerulationsa | Hunner lesionsb | |

| Biopsy | ||||

| Not done | XX | 1X | 2X | 3X |

| Normal | XA | 1A | 2A | 3A |

| Inconclusive | XB | 1B | 2B | 3B |

| Positivec | XC | 1C | 2C | 3C |

- a Glomerulations: grades 2–3 (grade 2, severe areas of submucosal bleeding; grade 3, diffuse bleeding of bladder mucosa).

- b With or without glomerulations.

- c Histology showing inflammatory infiltrates and/or detrusor mastocytosis and/or granulation tissue and/or intrafascicular fibrosis.

Appendix IV: Proposed treatment algorithm for BPS

Abbreviations: BCG Bacillus Calmette–Guérin; BPS bladder pain syndrome; DMSO dimethyl sulfoxide; MDT multidisciplinary team; MSU midstream specimen of urine; QoL quality of life; PPS pentosan polysulfate.

References

This guideline was produced on behalf of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists by:Dr SA Tirlapur MRCOG, London; Mrs JV Birch, Pelvic Pain Support Network, Poole; Dr CL Carberry MD, Providence, Rhode Island, USA; Professor KS Khan FRCOG, London; Dr PM Latthe MRCOG, Birmingham; Dr S Jha FRCOG, Sheffield, British Society of Urogynaecology; Dr KL Ward MRCOG, Manchester, British Society of Urogynaecology; Ms A Irving, Cystitis and Overactive Bladder Foundation, Birmingham

and peer reviewed by:

British Association of Urological Surgeons; Ms J Brocksom, British Association of Urological Nurses, Bathgate; Dr M Chaudry MRCOG, Leeds; Ms M Ding, Griffith University, Queensland, Australia; Mr B Kumar FRCOG, Wrexham; Dr A Leach, Bladder Pain Society, London; Professor L McGowan, University of Leeds; Dr BD Nicholson, University of Oxford; Dr JC Nickel, Kingston General Hospital, Ontario, Canada; Policy Connect, London; Mr R Thilagarajah, Whipp's Cross University Hospital, London.

Committee lead reviewers were: Miss N Potdar MRCOG, Leicester; and Dr BA Magowan FRCOG, Melrose, Scotland.

The chairs of the Guidelines Committee were: Dr M Gupta1 MRCOG, London; Dr P Owen2 FRCOG, Glasgow, Scotland; and Dr AJ Thomson1 MRCOG, Paisley, Scotland.

1co-chairs from June 2014 2until May 2014.

All RCOG guidance developers are asked to declare any conflicts of interest. A statement summarising any conflicts of interest for this guideline is available from: https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/guidelines-research-services/guidelines/gtg70/.

The final version is the responsibility of the Guidelines Committee of the RCOG.

Disclaimer

The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists produces guidelines as an educational aid to good clinical practice. They present recognised methods and techniques of clinical practice, based on published evidence, for consideration by obstetricians and gynaecologists and other relevant health professionals. The ultimate judgement regarding a particular clinical procedure or treatment plan must be made by the doctor or other attendant in the light of clinical data presented by the patient and the diagnostic and treatment options available.

This means that RCOG Guidelines are unlike protocols or guidelines issued by employers, as they are not intended to be prescriptive directions defining a single course of management. Departure from the local prescriptive protocols or guidelines should be fully documented in the patient's case notes at the time the relevant decision is taken.