Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy – Diagnosis and management: A consensus statement of the Society of Obstetric Medicine of Australia and New Zealand (SOMANZ): Executive summary

Conflict of interest: Prof Hague, Prof Callaway, A/Prof Middleton, Prof Peek, Dr Shand and A/Prof Stark are all CIs on an MRFF-Clinical trials and registries funding grant in 2018 (APP1152418) ‘Treatment of Severe Early Onset Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy’. None of the other authors have any conflict of interest to report.

KEY POINTS

- Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) is a pregnancy liver disease, characterised by pruritus and increased total serum bile acids (TSBA), Australian incidence 0.6–0.7%.

- ICP is diagnosed by non-fasting TSBA ≥19 μmol/L in a pregnant woman with pruritus without rash without a known pre-existing liver disorder.

- Peak TSBA ≥40 and ≥100 μmol/L identify severe and very severe disease respectively, associated with spontaneous preterm birth when severe, and with stillbirth, when very severe.

- Benefit-vs-risk for iatrogenic preterm birth in ICP remains uncertain.

- Ursodeoxycholic acid remains the best pharmacotherapy preterm, improving perinatal outcome and reducing pruritus, although it has not been shown to reduce stillbirth.

INTRODUCTION

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) is a pregnancy-specific liver disease,1 Australian incidence 0.6%–0.7%, characterised by pruritus and increased total serum bile acids (TSBA), after excluding other hepatic causes of pruritus.2 Important fetal complications include spontaneous preterm birth and stillbirth, but recent research has clarified the risk of stillbirth to increase only after 38 weeks when peak BA are 40–99 μmol/L, and from 35 weeks when peak BA are 100 μmol/L or greater.3 Maternal manifestations resolve postpartum.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

There is considerable ethnic variation in the incidence/prevalence of ICP,4 while a family history also increases the risk ten-fold.5

Rare genetic variants of BA transporters are reported in some ICP women,6 while recent genome-wide association studies have identified common sequence variation in liver-enriched genes and regulatory elements as contributing mechanisms to ICP susceptibility.7

ICP is more frequent in multiple pregnancy, with positive hepatitis C serology, and frequently accompanied by cholelithiasis,4 but these diagnoses do not exclude an ICP diagnosis.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Good practice points: The main symptom is pruritus, variably mild to very severe, affecting sleep and mentation.8 Typically distributed to palms/soles, it can become generalised.9 There is no rash; however, excoriations are common.

Urine may be dark. Jaundice and steatorrhea rarely occur. Commonly presenting after 28 weeks, 5% of cases occur in the first trimester.

DIAGNOSIS

Good practice point: ICP can be diagnosed in a pregnant woman with pruritus with non-fasting TSBA ≥19 μmol/L, a reliable threshold for diagnosis with good sensitivity and specificity,10 in the absence of other known active hepatic pathology.

Fasting TSBA ≥10 μmol/L can identify mild disease, with greater specificity but lower sensitivity (<30%).10Good practice points: Alanine transaminase (ALT) measurements are unnecessary for diagnosis and are poor markers of itch and pregnancy outcome. Increased TSBA should suggest considering other diagnoses (Table 1). A careful medical/obstetric history, with a full examination, are required.

| Differential diagnosis | Typical presentation | Features differing from intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) |

|---|---|---|

| Pregnancy-specific causes of itch not pre-existing (which do not exclude the diagnosis of ICP) | ||

| Atopy in pregnancy | Usually first trimester but can be any gestation |

Dry skin, eczematous rash, typical distribution in trunk and limb flexures May have pre-existing history of atopy |

| Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy | Itchy rash usually second and third trimester, typically around the umbilicus |

Papules and plaques, often target lesions. Usually affecting lower abdomen with umbilical sparing Normal serum transaminases |

| Pruritic folliculitis of pregnancy | Usually, third trimester |

Acneiform eruption, shoulders, upper back, thighs and arms, follicular in nature, maybe pus-filled Rash improves with advancing gestation |

| Pemphigoid gestationis | Usually, third trimester | Rare, blisters developing, not responsive to ICP therapy |

| Allergic/drug eruption | Pruritus and rash, any gestation |

Maculopapular rash, history of drug or allergen exposure May have abnormal transaminases or increased serum creatinine |

| Other systemic disease | Pruritus and rash, any gestation |

Signs and symptoms of systemic disease History of pre-existing disorder |

| Pregnancy-related liver disorders (which do not exclude the diagnosis of ICP) | ||

| Hyperemesis gravidarum |

Nausea and vomiting, first trimester, worse in multiple gestation Often following assisted reproduction |

No itch or rash Mild to moderate increase in serum transaminases |

| Acute fatty liver of pregnancy (AFLP) | Nausea, vomiting, jaundice, headache, abdominal pain, usually third trimester | Acute malaise, frequently with acute thirst and polyuria (transient diabetes insipidus), associated with renal and hepatic impairment, coagulopathy, hypoglycaemia, pancreatitis |

| Haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelets (HELLP) syndrome | Hypertension, proteinuria, headache, epigastric pain, second or third trimester | Hypertension, proteinuria, not typically associated with itch or rash |

| Liver disorders independent of pregnancy (excluding the diagnosis of ICP) | ||

| Viral hepatitis | May be acute or chronic | Typical viral serology |

| Primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) | Fatigue, pruritus | Positive anti-mitochondrial antibodies (AMA) |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) |

May be asymptomatic, but pruritus common, often associated with inflammatory bowel disease, especially ulcerative colitis May overlap with AIH |

Non-specific autoantibodies and abnormal immunoglobulins Typical bile duct ‘beading’ on magnetic resonance cholangio-pancreatography |

| Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) | Less likely to have rash, may have itch, associated with family or personal history of autoimmune disease | Positive autoimmune serology: Antinuclear antibodies (ANA), smooth muscle and/or liver-kidney microsomal (LKM) antibodies, and/or positive liver immunoblot |

| Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) | Nausea, vomiting, jaundice, abdominal pain, diarrhoea | Consider both prescription and non-prescription agents, including paracetamol, antibiotics, labetalol and methyldopa, alcohol abuse, herbal remedies and ingestion of various fungi |

| Biliary obstruction | Nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain | Liver ultrasound usually demonstrates features consistent with biliary obstruction |

| Veno-occlusive disease | Jaundice and fluid retention | Usually a complication of chemotherapy |

Conditional recommendation: If gestational pruritus persists with normal TSBA, repeat testing is indicated 1–2 weekly to reassess the diagnosis of ICP. 11

Previous childhood jaundice with pruritus (non-infective, post-neonatal) and/or oral contraceptive-related pruritus/jaundice warrants consideration of genetic causes.

Good practice points: Autoimmune liver disease rarely presents in pregnancy. A family history of autoimmune disorders (eg, thyroid, rheumatoid, type 1 diabetes mellitus), TSBA ≥ 40 μmol/L, or transaminases > 200 U/L (5× upper limit of normal) or presentation prior to 34 weeks, warrants an autoimmune screen (Table 2).

| Test | Rationale, interpretation |

|---|---|

| Serum biochemistry |

A rise in serum transaminases (ALT, AST) using pregnancy-specific ranges is commonly seen in ICP but is not diagnostic. Other biochemical disturbances may include abnormalities in gamma-glutamyl-transferase (γGT) (uncommon, and may reflect a specific subset of women), and bilirubin (rare). Pregnancy-specific reference intervals must be applied to results where appropriate, as must the clinical setting, eg, hypertension or fever |

| Glucose tolerance testing |

A 75 g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) should be performed as standard. There is an increased incidence of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) in ICP Consideration may be given to a reassessment of normal glucose tolerance following a diagnosis of ICP, especially if fetal macrosomia is suspected, or ICP is occurring sufficiently preterm for glucose control to be of benefit, using standard reference ranges |

| Urinalysis | Check for proteinuria (spot urine protein/creatinine ratio) each visit. There is an increased risk of pre-eclampsia in ICP |

| Coagulation studies | Prothrombin time (international normalisation ratio: INR) and activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) may be prolonged in severe cases, associated with malabsorption of vitamin K. This is particularly important in women who develop steatorrhea |

| Upper abdominal ultrasound | Exclude obstructive biliary disease in women with abdominal pain or fever. Gallstones (often asymptomatic) and biliary sludge are also seen more commonly in women with ICP and may merit surgical review postpartum if present |

| Fetal ultrasound | Monitor fetal growth with ultrasound if there are other complications, in particular, GDM and pre-eclampsia |

| Liver biopsy | NOT required, unless other significant pathology is suspected and management would be altered by the biopsy results |

| Viral serology | Hepatitis A, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) can be tested if there is clinical suspicion, including repeat testing if earlier antenatal screening tests have been performed |

| Autoimmune serology |

Anti-smooth muscle, anti-LKM (liver, kidney microsomal) antibodies and antinuclear antibodies (ANA) (chronic hepatitis), anti-mitochondrial antibodies (primary biliary cholangitis) can be performed in early onset (<30 weeks) or atypical ICP. In otherwise typical ICP, reserve such testing for those women in whom TSBA testing at/after 6 weeks postpartum does not resolve An autoimmune liver blot may also be useful (good sensitivity) |

An acute viral screen can be considered if there is clinical suspicion (Table 2).

Anorexia, malaise and vomiting suggest other disorders, eg, acute fatty liver of pregnancy, occasionally seen alongside ICP.12 Good practice points: Australian data report a threefold increase in risk of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), and a ten-fold increase in the risk of pre-eclampsia, with ICP.2

CONSEQUENCES OF ICP

Recommendation: The risks of preterm birth and stillbirth should be identified, depending on the peak TSBA titre,3 but a fall in TSBA from a peak value does not indicate a definite risk reduction.

Recommendation: Severe ICP should be diagnosed in women with peak TSBA ≥ 40 μmol/L, which is associated with increased spontaneous preterm labour, meconium-stained liquor and fetal asphyxial events. 13

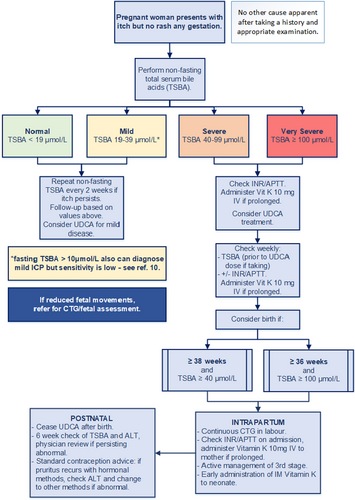

Recommendation: Very severe ICP should be diagnosed in women with peak TSBA ≥ 100 μmol/L, which is associated with an increased risk of stillbirth (hazard ratio (HR) 30.50; 95%CI 8.83–105.30; P < 0.0001)3 (Figure 1).

MANAGEMENT

Good practice point: Depending on severity and gestation at presentation, pharmacological options may not be required, given their uncertain benefit.14 The risks of spontaneous preterm birth vs those of preterm intervention merit careful consideration with both increased in severe disease.Good practice point: Most women with ICP, especially mild disease, show progressive TSBA reduction as pregnancy progresses, even without treatment.15

PHARMACOLOGICAL OPTIONS

Recommendation: If treatment in pregnancy is thought worthwhile, oral ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) can be recommended, with its varied possible modes of action.14 Dosage is based on severity, initially 500 mg/day in mild cases, or 1500 mg/day in severe cases, using twice-daily dosing regimens, increasing weekly to a maximum 2000 mg/day (20 mg/kg).15 Good practice point: Compared with placebo, UDCA results in a small improvement in pruritus.14 While the 25% itch reduction was not thought helpful by women in the PITCHES trial,15 clinically some relief of itch is better than none, and may reduce demands for premature birth.

Good practice points: A recent systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis reported no effect of UDCA on the prevalence of the composite outcome of stillbirth and preterm birth (odds ratio (OR) 1·28, 95% CI 0·86–1·91; P = 0·22). However, preterm birth, as well as the composite, was reduced when the analysis was restricted to the four available randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (OR 0·60, 95% CI 0·39–0·91; P = 0·016).16

With the event-rate for stillbirth alone in these studies being very low (1/439 compared with 3/429), no adequately powered study has yet assessed an effect on stillbirth rate.16

Availability and cost of UDCA may differ by country and region. In New Zealand, practitioners can apply for a subsidy by special authority for treatment of ICP. In Australia, UDCA is not listed on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme for treatment of ICP, but most public hospitals will provide subsidised access for eligible patients. Alternatively, a private prescription for UDCA can be taken to any community pharmacy for dispensing (noting the considerable out of pocket cost associated with this approach).

Other treatment options

Rifampicin shows benefit over placebo with a low incidence of adverse events in non-pregnant patients with cholestatic pruritus, and reduced TSBA,17 and is recommended in evidence-based guidelines as part of a stepwise therapeutic approach.18 An ongoing RCT, (ANZCTR 374510), is currently comparing rifampicin with UDCA for reduction of pruritus in ICP.19

Other treatment options, recommended in the same guidelines in non-pregnant patients,18 include the anion-exchange resin cholestyramine, the mu-opioid antagonists naltrexone and naloxone, and the serotonin-reuptake inhibitor sertraline. These should only be used in ICP under supervision by experienced clinicians.

Good practice points: Antihistamines, including cetirizine 10 mg once or twice a day and/or promethazine 25 mg at night, may provide relief from pruritus; however, these are untested in RCTs. Sedating antihistamines may aid sleep.

Good practice point: There are no trials of the efficacy of topical emollients, although these are likely safe, useful adjuncts.

Hot showers and scratching/rubbing the skin should be avoided. Plain moisturising lotion, liquid paraffin, pine-tar solution, aqueous cream with menthol, or sodium bicarbonate baths may provide symptomatic relief.

ANTENATAL

Multidisciplinary management is essential. Good practice points: Urgent referral and consult/transfer of care should be arranged in severe/very severe cases, with continuing maternity care at a referral centre, especially for cases before 36 weeks, or where there are other morbidities (eg, GDM or pre-eclampsia) or multi-fetal gestation.

After diagnosis of ICP, TSBA should be assessed with regular clinical review (at least monthly up to 30 weeks, fortnightly in the third trimester, or weekly in severe cases) (Fig. 1). Rapidly rising TSBA at this gestation might impact decisions about early birth. Once TSBA reach ≥100 μmol/L, there is no value in further testing to identify additional risk. If UDCA is commenced, blood should be drawn for TSBA shortly before the next dose: UDCA, itself a BA, may contribute up to 60% in the assay,20 although fasting is not required.

Prothrombin time/international normalised ratio (PT/INR) and/or activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), should be measured after diagnosing severe/very severe ICP, and repeated before induction of labour. INR ≥1.4 or APTT ≥ 40 sec require treatment with intravenous (IV) vitamin K 10 mg with further weekly assessment.

Oral vitamin K may be ineffective due to poor gastro-intestinal absorption.

BIRTH PLANS

Good practice points: Birth plans should be made in consultation with the woman, including discussion of risks-vs-benefits of planned birth < 39 weeks, if:

- severe ICP (peak TSBA ≥ 40 μmol/L) ≥ 38+0 weeks

- very severe ICP (peak TSBA ≥ 100 μmol/L) ≥ 36+0 weeks3

(Some authorities recommend earlier delivery for women with very severe ICP (eg, 35–36 weeks):21 the evidence-base for this is not strong.)

Risk of stillbirth for TSBA 40–99 μmol/L is 0.28% (comparable to background rates). This risk of stillbirth increases to 3.4% when TSBA exceeds 100 μmol/L, most notably from 35 to 36 weeks.3

ANTENATAL ADMISSION

Good practice points: Outpatient management is recommended if TSBA < 40 μmol/L and the woman remains clinically well.Admission for assessment and planned birth may be considered if TSBA ≥ 100 μmol/L, especially after 36 weeks. For those in rural/regional areas, consultation with a referral centre will inform management. Further outpatient management can be considered if treatment reduces the TSBA to <40 μmol/L.

Further research is required to determine if timing of birth may be modified by the response to treatment.

FETAL SURVEILLANCE

Good practice point: In the absence of other maternal/fetal pregnancy complications, growth ultrasounds and cardiotocography (CTG) are not required.

Cord Doppler flow measurements have not demonstrated changes, nor prediction of fetal risk, in ICP pregnancies.22Good practice point: Decrease/absence of fetal movements needs urgent review and is an indication for fetal assessment/CTG.

INTRAPARTUM MANAGEMENT

Good practice point: Continuous electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) intrapartum should be offered to women with severe/very severe ICP.

(Most women with severe ICP do not go into term spontaneous labour and are usually birthed electively. Thus, they are offered EFM intrapartum for reasons other than ICP.)

Good practice points: Coagulation should be checked in women with severe/very severe ICP with parenteral vitamin K (10 mg IV) administered if PT/INR or APTT are abnormal.

Active management of the third stage of labour is recommended, although reports of increased risks of postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) in ICP are conflicting.23, 24

Parenteral vitamin K should be administered to all neonates of women with ICP, especially if their mothers were treated with rifampicin or cholestyramine.25

POSTPARTUM MANAGEMENT

Maternal: Good practice point: cease pharmacological treatment at birth.Pruritus usually resolves 1–2 days postpartum. Maternal jaundice usually resolves in the first postnatal week.

TSBA commonly normalise within a week but should be checked, along with serum transaminases, at six weeks postpartum. Good practice point: Should biochemical abnormalities persist, investigation to exclude underlying liver disease is required.

Good practice points: Hormonal contraception is not contraindicated. If pruritus recurs in women using hormonal contraception, further investigation is required. Non-hormonal contraception should be considered if liver function remains abnormal.

Neonatal: routine care and monitoring are required.

COUNSELLING

Neonatal outcomes: once delivered, good outcomes can be expected.

Long-term outcomes: few studies have investigated long-term outcomes for children of pregnancies complicated by ICP.

Long-term maternal outcomes: the risk of ICP recurrence in a subsequent pregnancy is 40%2 to 70%.26 Recommendation: Women experiencing severe ICP, are at risk of chronic liver disease and should have long-term follow-up. While pruritus usually resolves postpartum, affected women have an increased risk of later hepatobiliary disease, including liver and biliary-tree cancer, and later immune-mediated diseases – diabetes mellitus, thyroid disease, psoriasis, inflammatory polyarthropathies, Crohn's disease (all with hazard ratios of 1.3–1.5).27 There is no consensus on appropriate follow-up. Good practice point: An annual check of liver biochemistry seems prudent.

INFORMATION FOR WOMEN

ICP Support is a group based in the United Kingdom with an up-to-date website (www.icpsupport.org) that provides information about ICP and its clinical impact based on published research. This group provides direct and indirect support to consumers via Facebook pages and groups, online meetings via Zoom, and worldwide email support, as well as providing ICP research updates to health professionals.

METHODS

The Society of Obstetric Medicine of Australia and New Zealand (SOMANZ) commissioned a consensus statement to provide practical guidance to clinicians caring for women with ICP (full version available on https://www.somanz.org/guidelines). Following an English literature review (2000–2021), a consensus of expert opinion was achieved, grading the recommendations (Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008; 336: 924–6.), and highlighting ‘Evidence-based recommendations with an assessment of the strength of the evidence’, from systematic review and meta-analyses, Conditional recommendations, where the evidence is not as strong, and ‘Good practice points’ where evidence is not available, (Table 3) (see Table 4 for key).

| GRADE: certainty and recommendation | ||

|---|---|---|

| DIAGNOSIS AND CLASSIFICATION of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) | The main maternal symptom is pruritus, ranging from mild to very severe, affecting sleep and mental state. The typical initial distribution is to palms and soles but can progress and become generalised. There is no rash but excoriations are common | |

| Base diagnosis of ICP on a non-fasting total serum bile acid (TSBA) concentration ≥ 19 μmol/L in the absence of pre-existing liver disorders in a pregnant woman with pruritus without a rash10 |

LOW: CONDITIONAL RECOMMENDATION |

|

| Alanine transaminase (ALT) measurements are unnecessary for diagnosis and are poor markers of itch and pregnancy outcome. Increased TSBA should suggest consideration of other diagnoses, with other liver abnormalities (Table 1) | ||

| Identify severe ICP in women with a non-fasting peak TSBA ≥ 40 μmol/L, with increased risks of spontaneous preterm labour, meconium-stained liquor and fetal asphyxial events 13 |

MEDIUM: RECOMMENDATION |

|

| Identify very severe ICP in women with a non-fasting peak TSBA ≥ 100 μmol/L, with a small but increased risk of stillbirth |

MEDIUM: RECOMMENDATION |

|

| A careful previous medical, obstetric and social history needs to be taken, including any pre-existing liver disease, alcohol and/or drug use | ||

| In pregnant women with ongoing pruritus without rash, but normal TSBA, repeat testing is indicated every 1–2 weeks, to establish or refute the diagnosis of ICP11 |

VERY LOW: CONDITIONAL RECOMMENDATION |

|

| In women where a diagnosis of ICP is being considered prior to 30 weeks gestation, or in severe/very severe ICP (peak TSBA ≥ 40/≥100 μmol/L) or where transaminases exceed 200 U/L (5× upper limit of normal), an autoimmune screen should also be conducted (see Table 2) | ||

| If there is clinical suspicion, women, in whom a diagnosis of ICP is being considered, should have viral hepatitis serology checked or repeated (see Table 2) | ||

| Women with severe/very severe ICP (peak TSBA ≥ 40/≥100 μmol/L) should be warned of the increased risk of spontaneous preterm labour | ||

|

MANAGEMENT |

Pharmacotherapy may not be required, especially after 36 weeks | |

|

MATERNAL ANTENATAL |

Use ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) in women who are not close to term to improve perinatal outcomes (composite of stillbirth and preterm birth) while also reducing pruritus 16 |

MEDIUM: RECOMMENDATION |

| Antihistamines are untested in clinical trials but may provide some relief of pruritus, and/or aid sleep | ||

| Topical emollients are likely to be safe and may be useful adjuncts in treatment | ||

| Ongoing measurement of TSBA should be performed, at least monthly up to 30 weeks gestation, every 2 weeks in mild ICP in the third trimester, and weekly in severe/very severe ICP (TSBA ≥40/≥100 μmol/L), using non-fasting samples, drawn shortly before the next dose of UDCA (if being used)10 |

LOW: CONDITIONAL RECOMMENDATION |

|

| Multidisciplinary involvement is essential. General practitioners, obstetricians and midwives should refer and share care for women in mild cases. If the condition presents early (before 36 weeks gestation) or becomes severe/very severe (TSBA ≥40 / ≥100 μmol/L), referral to an experienced clinician is beneficial | ||

Plans for birth should be made in consultation with the woman, including discussion of the risks and benefits of planned birth < 39 weeks, if:

|

||

| Prothrombin time / international normalisation ratio (PT/INR) and activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) should be checked in women with severe/very severe ICP (TSBA ≥ 40/≥100 μmol/L), and in women being treated with drugs that inhibit dietary vitamin K uptake, such as cholestyramine and rifampicin. Parenteral vitamin K (10 mg intravenous) should be administered if either are abnormal. The tests should be repeated weekly until delivery, and further parenteral vitamin K administered as indicated | ||

Outpatient management is recommended if

|

||

| Outpatient management can be considered if treatment reduces TSBA to <40 μmol/L | ||

| Screen for gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), which is associated with ICP, and consider rescreening after a diagnosis of ICP | ||

| Watch for hypertension and check for proteinuria, given the association of ICP with pre-eclampsia | ||

| FETAL ANTENATAL | Regular cardiotocography (CTG) monitoring is not required, except when other pregnancy complications (pre-eclampsia and/or GDM and/or fetal growth restriction) are present | |

| Monitoring fetal growth/wellbeing with serial ultrasounds is not required in the absence of other complications (eg, GDM and pre-eclampsia) | ||

| Any decrease/absence of fetal movements is an indication for immediate fetal assessment and CTG | ||

| MATERNAL PERIPARTUM | Admission for assessment and plans for birth are recommended if TSBA are ≥100 μmol/L, especially after 36 completed weeks of gestation | |

| PT/INR and APTT should be checked in labour in women with severe/very severe ICP (TSBA ≥ 40/≥100 μmol/L), and parenteral vitamin K (10 mg intravenous) administered if either are abnormal | ||

| Active management of the third stage of labour is recommended, given the possible risk of postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) | ||

| FETAL PERIPARTUM | Continuous electronic fetal monitoring in labour is recommended for women with severe/very severe ICP (TSBA ≥ 40/≥100 μmol/L) | |

| INFANT POSTNATAL | Intramuscular vitamin K should be administered to all neonates of women with ICP, especially if their mothers have been treated with rifampicin25 or cholestyramine28 | |

| MATERNAL POSTNATAL | Cease pharmacological treatment at or shortly after birth | |

| Check TSBA and serum ALT at six weeks postnatally. If biochemical abnormalities persist, further investigations should be performed to exclude underlying liver disease | ||

| Hormonal contraception is not contraindicated in women who have experienced ICP, but if pruritus recurs in those using hormonal contraception, further investigation should be undertaken. Consideration should be given to using non-hormonal methods of contraception if liver function remains abnormal | ||

| Women who have experienced severe/very severe ICP have increased risks of later hepatobiliary disease including liver cancer and require long-term follow-up 27 |

MEDIUM: RECOMMENDATION |

|

| There is as yet no consensus on the follow-up required, but an annual check of liver biochemistry is a reasonable option | ||

| HIGH | Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect |

| MEDIUM | Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate |

| LOW | Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate |

| VERY LOW | Any estimate of effect is very uncertain |

| Grades of recommendations (GRADE) | |

| RECOMMENDATION |

At least one meta-analysis, systematic review or randomised controlled trial rated as HIGH and directly applicable to the target population: or A systematic review of randomised controlled trials or a body of evidence consisting principally of studies rated as HIGH directly applicable to the target population and demonstrating overall consistency of results |

| CONDITIONAL RECOMMENDATION | A body of evidence, including studies rated as MEDIUM or LOW, directly applicable to the target population, and demonstrating overall consistency of results |

| Good practice points | |

| Recommended best practice based on the clinical experience of the consensus development group | |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are very grateful to Michael Ritchie of MKR Productions for his excellent work in formatting the main document for publication; to Bec Smith, Marnie Aldred and Monica Diaz from the SA Health Perinatal Practice Guidelines office for their cheerful and ever-ready assistance and patience in producing the flow diagram in its numerous drafts; and finally to the inimitable and irrepressible Suzie Neylon in the SOMANZ office for keeping us all in line. Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Adelaide, as part of the Wiley - The University of Adelaide agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

FUNDING

There is no financial or material support to report.